Can You Swim the Skeena?

Swim the Skeena Challenge

Swim the equivalent of 690 km at the Terrace Aquatic Centre

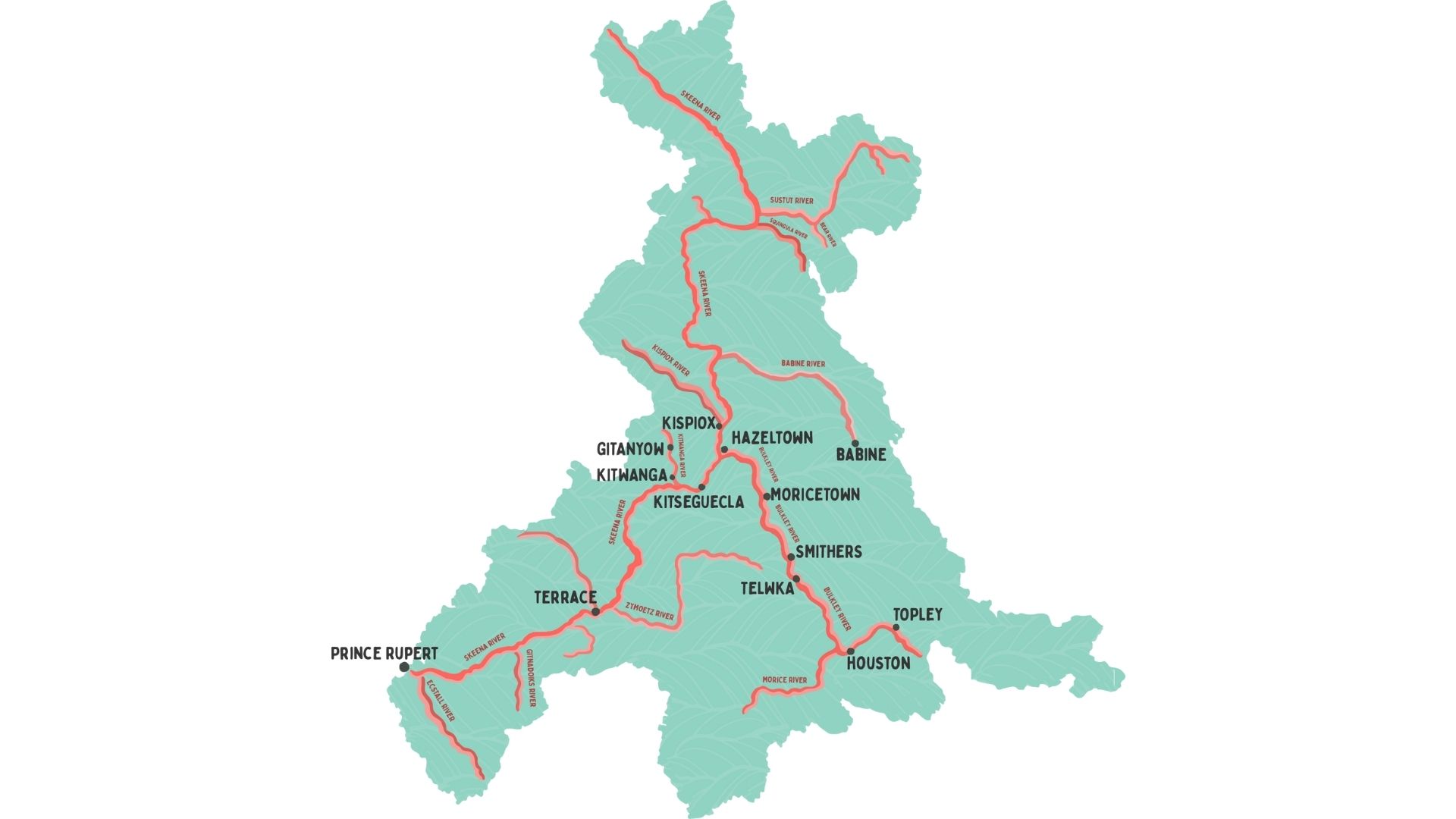

The mighty Skeena River runs 690km from the Sacred Headwaters (Spatsizi Plateau) to the Skeena Estuary near Prince Rupert, passing various stunning and essential sites.

Join this year’s ‘Swim The Skeena Challenge,’ a joint partnership with SkeenaWild and the City of Terrace.

Swim the equivalent distance of the Skeena River at the Terrace Aquatic Centre as we take you on a journey to learn about the spots along the way.

The Skeena River

The Skeena River is one of the most important and diverse in the world and home to five species of Pacific salmon and steelhead. People from around the world flock to the banks of the Skeena River every season just for a glimpse of these elite athletes of natural engineering, travelling thousands of kilometres throughout the Pacific Ocean, only to swim back to where they came from, spawn and die. The Skeena is one of the last remaining wild salmon strongholds. That’s why at SkeenaWild, we have hope: because we’ve already seen great things emerge when salmon are put at the centre.

Journey Down The Skeena Watershed With Us

Photo by Brian Huntington

KM 0: The Sacred Headwaters

This vast region in northern British Columbia is the birthplace of three iconic salmon watersheds: the Skeena, Stikine, and Nass Rivers. Local Tahltan people call the area Klabona, which loosely translates as “headwaters.”

The Sacred Headwaters is an area of cultural and ecological significance. But the region is also rich in mineral and energy resources, including coal and coalbed methane. Several industrial development projects were proposed for the area, such as Fortune Minerals’ open-pit Klappan Coal Mine and Royal Dutch Shell’s Klappan Coalbed Methane Project.

Between 2004 and 2009, Shell Canada proposed to develop thousands of wells to extract up to as much as 8.1 trillion cubic feet (230 km3) of coalbed methane gas.

These projects would have threatened the water supply and destroyed sacred cultural sites. Due to these threats and other community concerns, resource development in the Sacred Headwaters was halted. However, this victory was not without its challenges; a group of Tahltan elders and leaders were arrested for blocking the road leading to the proposed mine site. The arrests sparked a decades-long movement that eventually protected the area.

In 2019, The B.C. government and Tahltan Nation signed the historical Klappan land-use plan that advances reconciliation and embraces the Klappan Valley’s significant social, cultural, environmental, and economic values.

Collective community efforts helped safeguard vital salmon habitats and ensure the area’s cultural heritage is preserved for future generations.

The Upper Skeena

This part of the Skeena Watershed provides an important refuge for wildlife, hosts critical salmon habitat, and is largely untouched- despite some forestry, mining, and energy interest in the area.

The vast wilderness of the Upper Skeena Watershed presents a unique opportunity for achieving innovative conservation outcomes through Indigenous-led Land Use Planning. Examples of Indigenous-led land use plans in the region use enhanced land management standards that protect biological and ecological diversity, climate, and culture and consider future generations. These plans operationalize reconciliation and provide a clear path forward for how, when, and where development can occur to both minimize impacts and conflict.

Given that it is more cost-effective to protect intact forests rather than rebuild what has been lost, the vast wilderness of the Upper Skeena also presents exciting opportunities for carbon offset projects. These projects can play a crucial role in securing long-term protection of the area, helping the climate, and offering sustainable non-timber economic opportunities for local communities.

KM 337: Babine Confluence

The Babine watershed is a world-renowned system, marked by its rich ecology and cultural importance to the Indigenous communities who call Babine home. The Babine hosts a globally significant steelhead run and the Skeena’s largest population of Sockeye salmon, making it a critical part of the fishing and tourism industries. The Babine system supports important populations of moose, mountain goats and grizzly bears. Development pressures within the Babine watershed are growing as forestry cutting permits are issued to multiple large-scale licensees, and a pipeline corridor is proposed north of the Babine River. Watersheds like the Babine play a crucial role in climate regulation, carbon sequestration, and water management. Protecting systems like the Babine helps mitigate the impacts of climate change and ensure water availability for future generations.

KM 440: Witset

The Wetzin’kwa (Bulkley-Morice) is home to the Skeena watershed’s largest chinook salmon population and hosts sockeye, coho and steelhead. Witset (Moricetown) Canyon is renowned for its dramatic landscape and an important traditional Wet’suwet’en selective dipnet fishing site. The Wet’suwet’en also uses the Witset Canyon site to collect information on salmon returns and health, supporting essential conservation efforts in response to the diminishing returns of salmon returning to their territory due to climate change and worsened by land-use activities such as logging, mining, and agriculture. However, further upstream from the Witset Canyon, there is hope for salmon. While climate warming has negatively affected previously productive salmon systems, melting glaciers in the Upper Wetzin’kwa may create new suitable salmon habitats in the future.

Photo by Johnathon Patrick

Skeena & Bulkley Confluence

The confluence of the Bulkley and Skeena Rivers, located near the ancient village of Gitanmaax and present-day Hazelton, has long been an important meeting place for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

For millennia, this area has served as a vital fishing site and transportation hub for the Gitxsan people. The Village of Hazelton, often referred to as “Old Town,” has maintained its character since its founding in 1866. It has historically served as the central navigation hub of the region, evolving from a point along ancient trails to a location facilitating travel by canoes, pack trains, and dog sleds. Eventually becoming a stop for paddle-wheelers from the Northwest Coast.

Today, this area is not only a cultural treasure but also essential for salmon conservation. It supports all five species of Pacific salmon as well as steelhead trout, both of which are crucial for the health and sustainability of our communities that depend on these two significant rivers.

KM 511: Kitselas Canyon

Nestled along the banks of the Skeena River, Kitselas Canyon is home to the Gitselasu people of the Ts’msyen Nation. The rich cultural and archeological history of the canyon, coupled with its dramatic setting, led to a Canadian National Historic Site designation in 1972.

Archaeological evidence shows continuous habitation for at least 6,000 years. Once home to six ancestral villages, the canyon was a key transportation and trade hub. In Sm’algyax, Gitselasu means “People of the Canyon,” reflecting their role as toll-keepers for travellers on the Skeena.

Today, guided and self-guided tours offer a glimpse into the canyon’s rich cultural and historical significance.

This year saw the return of the Kitselas fishwheel to the Canyon—a selective fishing method used by Indigenous fishers for generations. Its revival symbolizes a meaningful step toward sustainable, community-driven food harvesting practices.

KM 521 Terrace

Terrace, BC, has long been shaped by the Skeena River and the salmon that sustain it. For millennia, the Kitselas and Kitsumkalum nations gathered here, relying on the river’s abundant salmon runs for food. The construction of the CN rail line and World War II further cemented Terrace’s role as a hub for trade and transportation.

Today, Terrace thrives as a vibrant and diverse community, with the Skeena River as its life-giving artery. It is renowned worldwide for its incredible salmon and steelhead fisheries. Anglers from around the globe fuel the local economy, supporting businesses and preserving traditions tied to these iconic fish.

As proud stewards of salmon conservation, our head office is located in Terrace. Stop by to check out our merchandise and learn more about how salmon continues to shape our community and its future.

KM 624: Tyee Test Fishery

Established in 1956 and operated by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), The Tyee Test Fishery provides one of the longest-running and most consistent data sets on salmon populations in the Skeena River.

Drift gillnets are set daily during the salmon migration season, typically from late June to early September. The captured salmon are identified by species, counted, and measured before being released. Other data collected include the number of fish caught, their size, and the timing of their return.

This information is vital for managing commercial, recreational, and Indigenous fisheries and conservation efforts.

The data is used by fisheries managers, scientists, and Indigenous groups to monitor trends in salmon abundance, assess the impacts of environmental changes, and develop strategies for sustainable fisheries management.

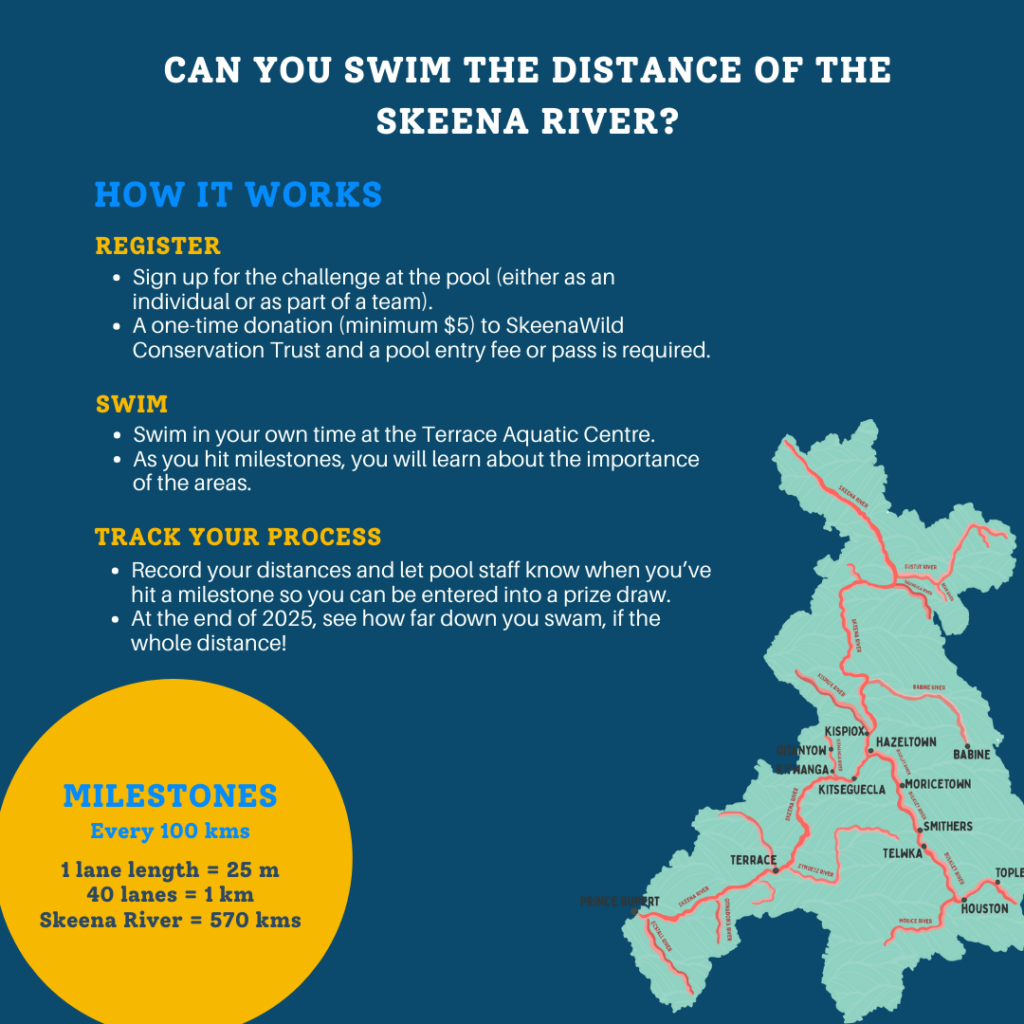

How To Join The Challenge

Location: Terrace Aquatic Center, 4540 Park Avenue, Terrace, BC, V8G 2N1.

- Sign up for the challenge at the pool (either as an individual or as part of a team). Registration is open all year round.

- A one-time donation (minimum $5) to SkeenaWild Conservation Trust is required plus a pool entry fee or pass is required. Paid at the pool.

- Swim in your own time and record your distances using the materials provided.

- As you hit milestones, you will learn about the importance of the areas.

- At the end of the year, see how far down you swam, if the whole distance! Start again the next year and make a new goal to work towards.

- Chance to win prizes for all involved.

Milestones – Every 100 kms

Make sure to let the pool staff know once you’ve hit a milestone so you can be entered into a prize draw.

- 1 lane = 25 m

- 40 lanes = 1 km

- Skeena River = 570 kms

Lane Swim Hours

- Monday to Friday:

6:00 am to 9:00 am (Passholders only)

11:30 am to 1 pm - Monday, Wednesday and Friday:

8:00 to 9:00 am - Saturday:

Noon to 1 pm - Sunday:

11:00 am to 1 pm

Our Story

Connecting Communities

Our Work

Salmon First

Other News

New Report Highlights Red Chris Mine’s Impacts and the Path to Responsible Mining in Northwest BC

SkeenaWild Conservation Trust’s independent investigative report illuminates key environmental concerns related to mining in northwest BC. The Red Chris Mine, an open pit copper-gold mine…

SkeenaWild Announces Julia Hill Sorochan as New Executive Director

SkeenaWild Conservation Trust is proud to introduce Julia Hill Sorochan as its new Executive Director. Following an extensive selection process by the Board of Trustees,…

Ecstall River Monitoring Update

In early fall 2022, a massive landslide tore through the Ecstall River watershed, sending a wave of rock, debris, and sediment downstream. The slide reshaped…

Addressing Seabridge Gold’s Misrepresentation of Key Facts

KSM Mine Update Addressing Seabridge Gold’s Misrepresentation of Key Facts Following The Legal Challenge Filed Against The BC Government’s Decision To Allow KSM Mine to…

New Report Highlights Red Chris Mine’s Impacts and the Path to Responsible Mining in Northwest BC

SkeenaWild Conservation Trust’s independent investigative report illuminates key environmental concerns related to mining in northwest BC. The Red Chris Mine, an open pit copper-gold mine…

SkeenaWild Announces Julia Hill Sorochan as New Executive Director

SkeenaWild Conservation Trust is proud to introduce Julia Hill Sorochan as its new Executive Director. Following an extensive selection process by the Board of Trustees,…

Ecstall River Monitoring Update

In early fall 2022, a massive landslide tore through the Ecstall River watershed, sending a wave of rock, debris, and sediment downstream. The slide reshaped…

Addressing Seabridge Gold’s Misrepresentation of Key Facts

KSM Mine Update Addressing Seabridge Gold’s Misrepresentation of Key Facts Following The Legal Challenge Filed Against The BC Government’s Decision To Allow KSM Mine to…