Southeast Alaska 2025 Salmon Season Summary

Southeast Alaska 2025 Salmon Season Summary

A worse than forecast pink return in Southeast Alaska put BC salmon back in the crosshairs

Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) had forecasted a catch of 29 million pink salmon, with the possibility of up to 53 million, ahead of the 2025 season. However, by the end of July, it was clear that pink returns to Southeast Alaska were much poorer than anticipated and the fishery needed to search further afield – for migrating Canadian salmon in District 104 – to stay afloat.

The season-end catch came in at just over 20 million pink salmon, similar to in 2024, with the purse seine fleet landing ~19 million—ten million short of the forecast and over 25 million fewer than in 2023 (the parent year for 2025 pinks). But it’s when – and where – the catch occurred that matters…

| 2025 Catch Forecast | 2025 Commercial Catch | 2024 Commercial Catch | |

| Pink Salmon | 29 million | ~20.7 million | ~ 20.1 million |

| Chum Salmon | ~ 15.5 million | ~13 million | ~ 15.7 million |

| Coho Salmon | ~ 1.5 million | ~1.4 million | ~ 1.3 million |

| Sockeye Salmon | 886,000 | 751,000 | 776,160 |

| Chinook Salmon | 103,000 | 154,000 | 197,863 |

Figure 1: Preliminary Southeast Alaska commercial catch by species compared to pre-season catch forecasts and commercial catch in 2024 (Alaska Department of Fish and Game).

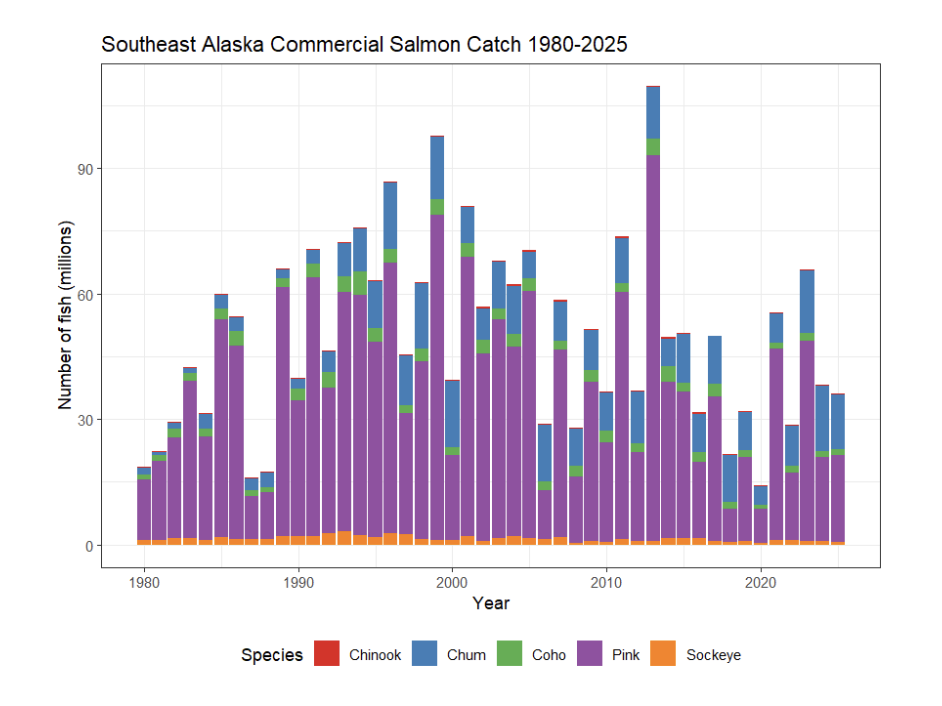

Southeast Alaska commercial salmon catch by species for 1980-2025 (Alaska Department of Fish and Game). Catch numbers for 2025 are preliminary.

The Turning Point: July 31st

Facing a very poor pink season in Southern Southeast Alaska (SSE), Alaska created opportunities for the fishing fleet to intercept Canadian fish. During a pivotal, extended opening beginning July 31st, most of the SSE fleet abandoned traditional fishing areas in Alaska’s inside waters and poured into District 104 – on the outside of the Alaskan panhandle – to intercept migrating Canadian salmon.

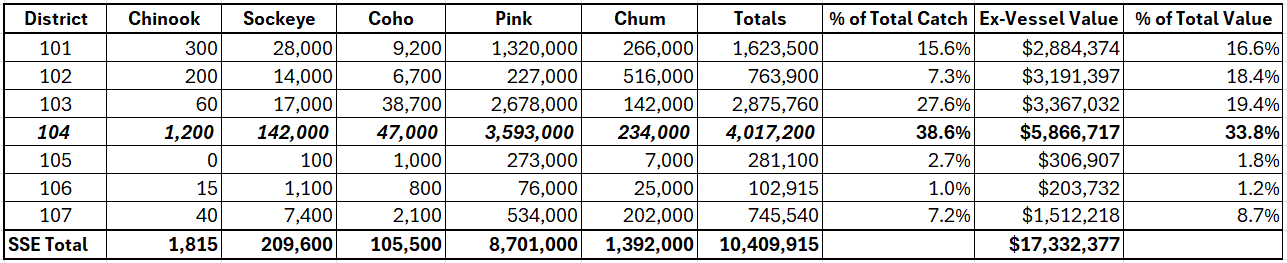

Over the four days that followed, 2.7 million salmon were caught in this district alone. By season’s end, it was over 4 million salmon – nearly 40% of the total catch in SSE Alaska this year.

2025 salmon catch totals by species in the purse seine fishery in Southern Southeast (SSE) Alaska Districts 101-107 (Alaska Department of Fish and Game). Nearly 40% of the total catch came from District 104, which is located on the outside of the Alaskan panhandle and intercepts salmon migrating to rivers in British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon.

After July 31 – it’s ‘open-season’ on Canadian salmon

The date matters — under the Pacific Salmon Treaty, there are no catch limits for Alaska on Canadian sockeye after July 31st, and it’s the Skeena sockeye migrating through District 104 waters that attract the fleet out. Even though it is labelled a “pink salmon-directed” fishery, sockeye salmon have significantly more market value than pink salmon ($1.71 per pound compared to $0.26 per pound in 2025 according to ADFG). Over 140,000 sockeye were caught in District 104 this season – and on average, about 75% of those sockeye are headed for the Skeena.

It was the District 104 interception fishery, and deliberate management decisions to provide extended openings during a crucial migration window, that sustained Southeast Alaskan processors and the fishing fleet this year.

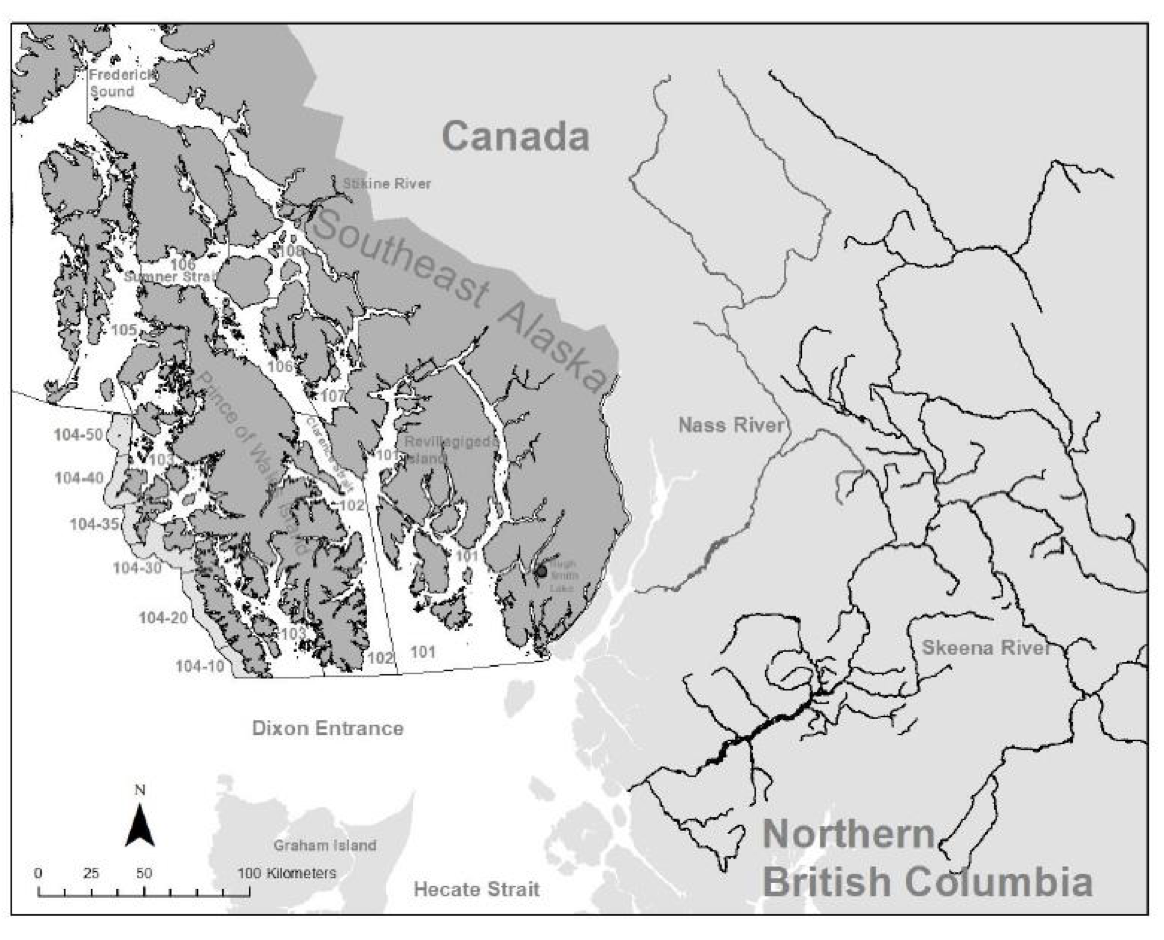

Southeast Alaska fishing districts 101-104 border Canadian waters in northern British Columbia, but District 104 is strategically located on the outside of the Alaskan panhandle, a known migration corridor for salmon bound for the Skeena, Nass, and other rivers in B.C.

Implications for Wild Salmon Recovery

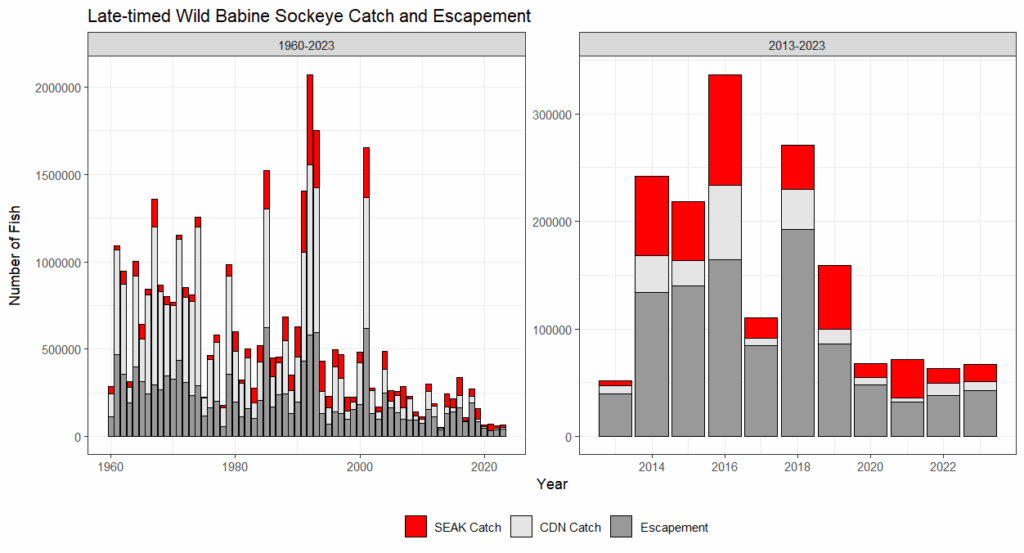

The timing of the sockeye catch in District 104 is particularly concerning for wild sockeye returning to the Babine watershed in the Skeena. Wild Babine sockeye have already declined in abundance by over 90%, yet are still heavily exploited in commercial fisheries. Recent estimates show the average exploitation rate has been around 39%—far above the estimated sustainable level of ~26%. Of this, Alaska accounts for ~28%, with Canada contributing ~11%. Estimates are based on run-timing reconstructions, as Alaska doesn’t share population-specific genetic data that would help Canada track the impact on its salmon.

Late-timed wild Babine sockeye escapement and catch estimates in Southeast Alaska and Canada from 1960-2023 (left) and 2013-2023 close up (right). The population has declined more than 90% in abundance and is still heavily impacted by commercial fishing in Southeast Alaska in recent years (data source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada).

Missing Data, Hidden Impacts

The damage is further obscured by critical data-reporting deficiencies. The full impact on B.C. Chinook and steelhead is unknown, as they are often caught as “bycatch” with no record.

In one opening in District 104 where Chinook retention was allowed, just 16 vessels reported catching over 1,000 Chinook. In the next opening, with 80 vessels on the water and retention closed, the reported catch was zero – an implausible figure that points to a dangerous blind spot in understanding the full impact of these fisheries.

Steelhead are not reported either, but recent estimates suggest that ~27% of the Skeena steelhead return, which was very poor this year, may have been killed in Southeast Alaska nets.

What’s Next?

While the Southeast Alaska purse seine fishing season has wrapped up, the commercial troll fishery, which targets Chinook and coho salmon, continues year-round and opened for early winter fishing on October 11. During the winter, the fishery targets non-Alaskan Chinook and endangered runs in Oregon, Washington, and B.C. pay the price. Read more on the impacts: https://watershedwatch.ca/stories/alaska-is-trolling-b-c-with-its-winter-chinook-fishery/

As Alaska continues to fish hard on the backs of Canadian salmon, calls are growing for stronger cross-border protections and transparency around the scale of these interception fisheries.

Time for Change

In January 2026, Canadian and American commissioners will begin negotiations for the 2028 renewal of the Pacific Salmon Treaty — a once-in-a-decade opportunity to address these cross-border impacts.

Here’s what needs to change:

• Move Alaska’s fisheries away from migration corridors where B.C. and lower U.S. salmon are intercepted, to rivers of origin in Southeast Alaska where local, abundant stocks can be targeted without harming other populations.

• Mandate full reporting of bycatch, including Chinook and steelhead.

• Implement transparent, fishery-independent monitoring to assess true catch impacts for target and non-target species.

• Share genetic data across borders so we can understand where fish are coming from — and how to protect them.

It’s time for the U.S. and Canada to work together on real solutions – based on science, transparency, and respect for shared ecosystems. It’s time to stand united for salmon.

B.C.: Don’t Buy Alaska Seafood

What you can do to defend B.C. Salmon

Sustainable Fisheries Management

We advocate for the development of abundance-based management plans for all species.

Other News

-

2025: Our year in Review

2025 Annual Report 2025: What We Achieved Together And what’s in store for 2026. Your support makes it all happen. Together, we’re building a sustainable…

-

Citizen Letter to an MP — Uphold the North Coast Oil Tanker Moratorium

The North Coast of British Columbia is one of the most ecologically rich, culturally significant, and irreplaceable coastlines in Canada. Our salmon rivers, wildlife, forests,…

-

SkeenaWild warns DFO cuts threaten salmon and communities that depend on them

The federal budget announced yesterday includes $500 million in cuts to Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) over four years. That’s five times deeper than the…

-

Southeast Alaska 2025 Salmon Season Summary

Southeast Alaska’s 2025 salmon season fell short of forecasts, with pink salmon catches down 10 million. A major fishing shift into District 104 raises new…

-

2025: Our year in Review

2025 Annual Report 2025: What We Achieved Together And what’s in store for 2026. Your support makes it all happen. Together, we’re building a sustainable…

-

Citizen Letter to an MP — Uphold the North Coast Oil Tanker Moratorium

The North Coast of British Columbia is one of the most ecologically rich, culturally significant, and irreplaceable coastlines in Canada. Our salmon rivers, wildlife, forests,…

-

SkeenaWild warns DFO cuts threaten salmon and communities that depend on them

The federal budget announced yesterday includes $500 million in cuts to Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) over four years. That’s five times deeper than the…

-

Southeast Alaska 2025 Salmon Season Summary

Southeast Alaska’s 2025 salmon season fell short of forecasts, with pink salmon catches down 10 million. A major fishing shift into District 104 raises new…