2024 Salmon Re-cap: Part Two, North and Central Coast

Breaking down salmon returns across diverse watersheds and species in British Columbia.

Written by Greg Taylor, Fisheries Advisor

Happy New Year and welcome to Part Two of my 2024 Year in Review. Breaking from tradition, I decided to write this year’s report in multiple sections. When I began drafting my recap late last year, one of the first things I wrote was about 2024’s good salmon returns. But as I did a deeper dive, I realized that if I said this outside of a historical context I would be contributing to our very human tendency to ignore shifting baselines at our peril. Salmon abundances were poor in 2024 compared to 40 years ago, and terrible compared to pre-contact times.

Greg Taylor, SkeenaWild and Watershed Watch’s Fisheries Advisor, has worked in the B.C. seafood industry for over 30 years and has chaired several industry associations and boards. Mr. Taylor is an advocate for sustainable salmon fisheries and works closely with several First Nations on fisheries issues.

Salmon Returns Across B.C.: Watersheds, Variability, and Urban Restoration Success

I would have also been wrong in that salmon returns were not consistently good across the province. Salmon returns varied by population, species, and watershed. It would have been lazy of me to say otherwise. After all, the Skeena Watershed is about the same size as Nova Scotia and the Fraser Watershed is about the size of the United Kingdom. Together the Nass, Skeena, and Fraser Watersheds are as large as Italy.

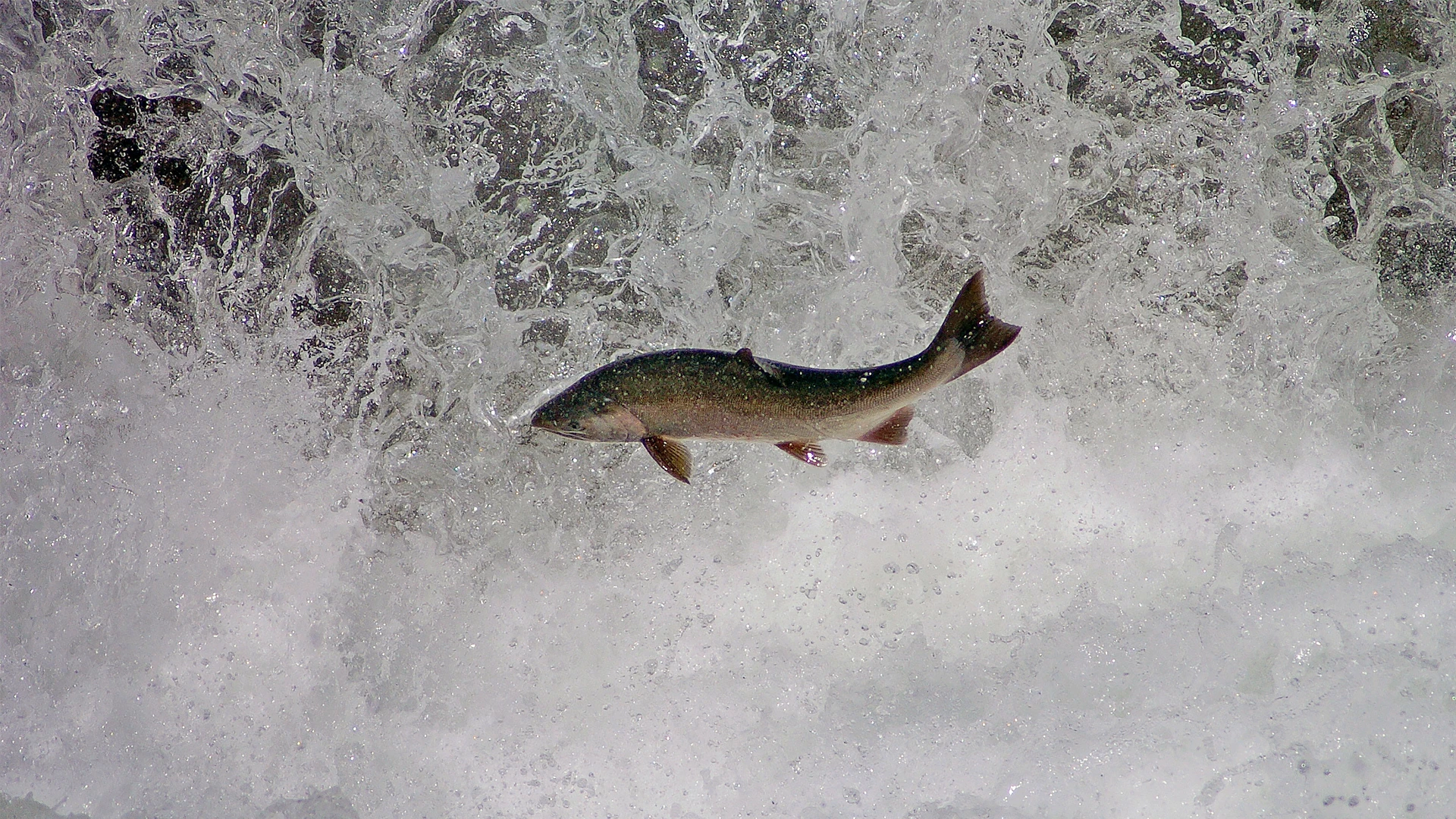

Added to our large watersheds are all the smaller watersheds that exist in myriads of micro- environments throughout our province. There is a little urban stream with a watershed that encompasses less than 5,000 hectares, that runs near my home in Victoria. It has been restored by the Peninsula Streams Society with funding from the Pacific Salmon Foundation. I watched this New Year’s Eve Day, as excited as the children alongside me, as we all took in the two male and one female coho completing their spawning rituals in a stream that most of the children could have splashed across in their gumboots. This urban stream is obviously enjoying the same good return of coho seen in most south coast streams.

But a streamkeeper on Haida Gwaii, commenting on Part One of my recap, reported that the streams he works on saw some of the worst chum returns in 10 years. Coho returns, at least in Area 2E on the east coast of Haida Gwaii, from the limited information available did not appear to be much better. And, as we will discuss later in Part Two, Early Stuart sockeye in the Upper Fraser saw just 26 adult sockeye return, compared to the 45,000 that returned in 1984 (a year when there were also significant commercial and Food, Social and Ceremonial (FSC) fisheries). And on the Skeena, where I will discuss the large return of enhanced sockeye, I will also speak to the bleak returns of co-migrating wild sockeye populations that spawn in the tributaries of the same lake.

With that cautionary introduction, I will review 2024 returns by region. For 2024 catches, please see the table in Part One. Before continuing, someone asked why I do not include FSC and Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) catches. It is a good question. I began this recap several years ago speaking only to commercial catches. I have only recently included recreational catches. I will incorporate FSC catches in the future. I will speak to IUU impacts, but, by their very definition, I cannot record the numbers caught in such fisheries.

Finally, I would like to note one recurring theme you will read in this report, just because the marine environment appears to have generated some positive returns for many populations. Our new climate means that an abundance of returning salmon does not necessarily translate into a similar abundance of spawners. A warming and changing freshwater environment can be challenging to salmon.

Areas 1 and 2 – Haida Gwaii

I remember inviting my Dad to join me to fish the Yakoun River at the top end of Haida Gwaii back in 1984. I was working for B.C. Packers buying razor clams and working in their troll plant. Dad and I were fishing for cutthroat at the end of the trail that wound its way around the famous Golden Spruce. It was the end of August, and the troll season was winding down. We went every afternoon after work and spent the evening rising cutthroat to dry flies. Near the end of the week, the reclusive cutthroat suddenly appeared to be everywhere. That is, until upon closer inspection, we discovered they were not cutthroat, but pink salmon. Thousands of pink salmon, filling the river from bank to bank.

I told the local fishery officer, which began a process that initiated the first pink salmon opening for seines in Masset Inlet in many, many years. Masset Inlet quickly filled with northern seine boats anxiously waiting for the opening. The night before it was to open, the inlet was filled with bunches of pinks finning and flopping, but on the morning of the opening there was nothing. Not a fish broke the surface. Masset Inlet looked like a windless pond. Fishers assumed DFO had waited too long and the fish had moved into the river. The radio chatter was not for the faint of heart.

DFO went ahead and opened the Inlet on the Marine VHF Radio at 06:00 as scheduled. Boats milled around without much enthusiasm as I watched anxiously from the dock at Port Clements. Finally, a boat set. As he drummed back you could see he had nothing. A second boat set. He caught a car that had been driven off the dock years before. It would take money the crew could ill afford to repair their net.

You could feel the mood of the fleet sag as crews added up the money it cost them in fuel and grub to come all the way over to Masset. After another 30 or 40 minutes of drifting around, a third boat set without much enthusiasm.

As soon as the crew closed up the net and pursed the rings, trapping the fish within the net, now alongside the boat, I could see, from my position up on the dock, bubbles throughout the net. By the time he had drummed half the net back it came alive with pink salmon. On boats throughout the inlet, black smoke poured from the long idling engines as skippers blasted their horns, signalling their skiffs to let go, intending to set before the boat alongside them did. Before the week was up the fleet had caught over a million pink salmon.

I tell this story, and I could tell more of the bountiful fall chum fisheries on Haida Gwaii. Stories of flying over in a small Cessna two or three days a week for 3 or 4 weeks from mid-September through early October to manage gillnet and seine fisheries in the various inlets on the east and west coast of Haida Gwaii. (It sounds like fun until you think about the flying weather in Hecate Straits in late September-early October).

I always thought the way DFO managed this area was the way most of the coast should have been managed and my hat is off to Pat Fairweather who was in charge of it. We did not fish until DFO determined a stream had sufficient spawners. We started to fish with a large boundary around the stream. The boundary would collapse as the necessary escapement target was secured in the stream. But I digress, my memories are of a Haida Gwaii with plentiful salmon.

I forecast a good pink salmon return to Area 1 in 2024, going as far as to urge Ocean Wise to add Area 1 seine-caught pinks to their recommended list in preparation for a fishery. Unfortunately, while pink returns were near target throughout Haida Gwaii, there were insufficient fish to trigger openings. I am hopeful we will see fisheries for Yakoun River pinks again in 2026 based on the number of this year’s spawners. I am not so hopeful for the other smaller pink salmon systems throughout Haida Gwaii. While they all also had good returns, there were extremely high levels of pre-spawn mortality because of low stream levels and high temperatures.

It tells a similar story to what we will see for Skeena sockeye and other north coast pink systems, as well as for Fraser sockeye. Salmon live in two worlds: a marine world and a freshwater one. Good marine productivity no longer necessarily translates into better spawner success. It is wonderful to see salmon return in abundance, but what we are often seeing now is that the impacts of climate change in a salmon’s freshwater environment can take what should have been a good return and convert it into a poor one. Haida Gwaii, like the rest of the planet, is a different place than it was 40 years ago.

Haida Gwaii chum returns, on the other hand, continued their decades-long trend of poor returns. I have no idea why Haida Gwaii chums have become much less abundant. My guess is the fry are not surviving their migration out of the inlets and into the near-shore marine environment.

Area 3 – Nass Region

The Nass Region incorporates the entrance to Portland Canal, the watersheds whose streams enter Portland Canal, and the Nass Watershed itself. Returns for all species, other than chinook, exceeded escapement goals. Sockeye, even-year pinks and chums saw particularly strong returns. The steelhead return, although not particularly strong, exceeded its escapement goal. Chinook continued the recent trend of poor returns and barely exceeded their minimum escapement goal. The total pink salmon return, including the coastal streams, is estimated to be over 1.6 million, which is an excellent return. Sockeye, too, were well above average.

You might then ask, why were commercial catches so poor? The forecast was for a below-average return for both species so managers were precautionary at the beginning of the season. As it became clear returns were much stronger than forecast, and DFO provided more opportunities, industry lacked the harvesting or processing capacity to respond. Finally, because DFO lacks good in-season escapement reconnaissance these days, they again became precautionary as the end of the pink salmon season neared. Processors were not advocating for more openings, due to the marketing issues described in Part One.

It should also be noted that Nass sockeye benefitted from reduced Alaskan exploitation in 2024. It was about 40 per cent of average. Skeena sockeye, as we shall see, also benefited. This was not due to any goodwill from Alaska. It was a result of a smaller proportion of Nass and Skeena sockeye making landfall on the Alaskan panhandle; something often seen when marine waters are cooler.

Area 4 – Skeena Watershed

Challenges in Managing the Skeena Watershed Fisheries

We have all heard the criticisms leveled at DFO managers. I am guilty of doing my share over the years. But put yourself in their shoes this salmon season. Managers know not to trust their pre-season forecasts, so they work in great uncertainty. They know that their one critical in-season assessment tool can be out by 30 per cent or more to either the upside or downside, and is only effective for estimating sockeye abundance. For other species, it only provides an evaluation of the current year relative to an index.

Meanwhile, DFO is charged with opening fisheries targeted on a few abundant species or stocks, while ensuring these same fisheries do not drive the much greater number of smaller and weaker salmon populations below sustainable levels.

Managers are tasked with achieving the above while also trying to satisfy the interests and demands of four major First Nations, commercial and marine recreational fishers, conservationists, steelhead guide/outfitters and local communities. And each of those interests are split, meaning none are necessarily advocating for the same thing as the other in their group. Now, throw in the uncertainty of climate change.

Balancing Competing Interests Across Stakeholder Groups

For instance, while I wrote that there are four major First Nations in the watershed, three have similar cultural and linguistic backgrounds; one comes from a remarkably different cultural and linguistic background. The Lake Babine Nation are Dakelh, or Carrier, people. The Tsimshian, Gitxsan, and Wet’suwet’en are coastal peoples. Over 85 per cent of Skeena sockeye return to territory belonging to the Lake Babine Nation (LBN) people. Most of these fish are artificially enhanced using massive engineered spawning channels. The majority of LBN’s wild sockeye populations, the ones they relied on for the past 8,000+ years, have crashed. Meanwhile, because of colonization, the other three First Nations’ access to salmon returning to their territories is severely compromised, meaning they, and other harvesters, have become hooked on enhanced sockeye, to the detriment of wild unenhanced populations throughout the watershed.

It is in this environment DFO managers must determine how to deliver harvesting opportunities to all the various groups while ensuring weaker stocks persist. I use the term ‘persist’ because there appears to be little intent to recover these populations. And this frightens me because a goal of having a population merely persist is likely insufficient in a time of rapid climate change and uncertainty.

SE Alaska Harvests and Their Impact on Skeena Salmon

What further increases managers’ challenge is that it is not B.C. harvesters that have the largest impact on many Skeena salmon populations. The proportion of the total catch of Skeena sockeye and coho (and most likely pink, chum, and steelhead) caught in Alaska is often much higher than it is in B.C. DFO managers are thus allocating what is left over after Alaska takes what it wants.

2024: A Better-than-Expected Return of Sockeye and Pink Salmon

The 2024 Skeena salmon season saw a much better than expected return of enhanced sockeye and pink salmon. But as 2024 proved, just because fish are available to catch in B.C., it does not mean they are going to be caught.

The gillnet fleet did not come anywhere close to catching their potential allocation. A combination of precautionary management, a lack of harvesting and processing capacity, and being forced to use inefficient gear and fishing practices to reduce bycatch meant that they caught less than half their potential sockeye allocation.

While seines caught their relatively small sockeye allocation, they did not come anywhere near catching their allowable catch of pinks due to restrictions to protect co-migrating species and a lack of processor interest.

Babine River Fence

The largest harvester of Skeena sockeye was the terminal fishery conducted by Talok Fisheries (owned by the Lake Babine Nation – LBN) in front of the Fulton River Enhancement Facility.

Over 2.1 million sockeye were counted coming into the lake through the Babine River Fence. About 480,000 were spawned in the Pinkut and Fulton spawning channels and their associated flow-controlled rivers. Another maybe 100,000 spawned in wild systems as 2024 saw another very poor return of Babine wild sockeye. Approximately 250,000 were caught in terminal fisheries and maybe 20,000 in recreational and in-lake FSC fisheries. It is unclear what happened to the other 1.25 million sockeye that passed through the fence and are unaccounted for.

A large number were enhanced fish that were locked out of the channels and died without successfully spawning. But I was engaged in Talok Fisheries’ terminal fishery and I can attest that neither I nor the professional coastal fishers from Prince Rupert who caught Talok’s sockeye saw any evidence of the million-plus missing fish. When we quit fishing, there were few sockeye seen either jumping, or on the boat’s sounders.

It is possible a significant number could have been lost to pre-spawn mortality and did not survive their migration to the spawning channels. When the fish arrive at the counting fence, the fence creates a solid barrier to migration as the fish are slowly counted through the fence. A large mass of red sockeye pile up behind the fence awaiting their opportunity to get through one of the seven small counting gates that are open only during the day. In 2024 the Babine River was abnormally low and warm; lethally warm at times. Research on the Fraser River has shown such events can create delayed mortality to those sockeye subject to extended periods of stress due to poor migratory conditions. Wild sockeye streams saw similar conditions as low water often delays entry and in-stream water temperatures were high.

One must credit the Lake Babine Nation. While everyone from Alaska through the Skeena watershed kept fishing for Babine sockeye, the Lake Babine Nation curtailed their fence fishery for food. To put this sacrifice into context, LBN people have been fishing for their food at this same spot, for over 8,000 years. LBN also began experimenting with using video cameras to enable them to count fish through the fence 24 hours a day.

Species-Specific Returns in the Skeena Watershed

As we have seen through this report, in the era of climate disruption, a large return of salmon does not necessarily translate into an equally large number of successful spawners.

Coho returns in the Skeena watershed were around the long-term average, but below the previous couple of years. There was an above average return of steelhead, confirmed by anglers, who saw consistent success other than the couple of weeks washed out by heavy rains. Even Skeena chums, although very depressed, saw a better return when compared to their disastrous brood years, although 2024 was still only about half the ten year average.

It was Skeena chinook that was the outlier. Skeena chinook saw what may be their worst return on record. This continues an almost 15-year downward trend. It is interesting how Alaskan and northern B.C. chinook abundance has diverged from southern B.C. and the U.S. states of Washington and Oregon, which have seen improving abundance in the last couple of years. This is not unusual. We have seen this in the past. A decline in chinook abundance often begins in their southern range and moves north over a decade or more.

Recovery also usually begins in the south and gradually moves north in response to changes in their marine environment. Will chinook abundance in the north eventually improve as many southern chinook populations have? All we can do is hope, while protecting the habitat and getting as many as possible back to spawn every year.

It may also, as we have seen in their southern range, depend on how much of a chinook population’s life cycle is spent in environments that escape the worst impacts of climate change. Those chinook that spend an extra year or more rearing in freshwater may continue to struggle. As I said at the beginning of the re-cap, one must beware of generalizing in the new world of climate uncertainty.

Central Coast: the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest, with over 290 salmon streams, stretching from the Skeena River in the north to Cape Caution in the south. Communities include Kitkatla, Hartley Bay, Kitimat, Klemtu, Kitasu, Bella Bella, and Bella Coola

Areas 5 and 6 – Kitkatla, Hartley Bay, and Kitimat: 92 salmon streams

I should make note that significant atmospheric rivers that hit the north and central coast early this fall may have washed away some of the newly laid eggs in some areas. The reasonable pink returns we saw, and the hope they gave me for continued future improvement, may have been washed away in the very high flows.

Did you know Area 6 in the Great Bear Rainforest has an angel? And this angel has a name, and it is Stan Hutchings. Stan, at 69, is one of the last of the charter patrolmen that used to monitor salmon streams throughout our coast. Daily, throughout the salmon season, Stan and his dog head out alone into streams that tunnel through the lush coastal rainforest to count returning salmon. He reports his findings to DFO managers who use this information to decide on whether there are sufficient salmon to open a fishery. But he also monitors the health of streams, reporting any concerns to the proper authorities. This year he reported development activity when there should have been none, triggering a response.

Stan then went on to re-cap the 15 streams he also walked that week along with salmon counts from each: alone, in bear country, among spawning salmon. Stan deserves a big thank you from everyone who cares about salmon.

Salmon returns were reasonable throughout Area 6, other than Kitimat hatchery chums. Both pinks and chums showed some improvements in many areas, not sufficient to trigger fisheries, but hopeful signs of continued slow recovery from the 2018 to 2020 period. Of course, these recoveries coincide with very limited fishing efforts in the area. It is unclear what the impact of the atmospheric rivers may have been on the smaller coastal systems.

It is interesting to note that many chum hatchery returns in Areas 6, 7, and 8 appear as bad, or worse, than wild returns throughout the Central Coast. One would think, considering the money invested in producing these hatchery fish, that the returns would be significantly better. It is unclear why the returns are so much poorer than expected. It could be for a similar reason as to what has happened in some chum hatcheries in Alaska. The release of fry is like ringing a dinner bell, attracting predators from humpbacks through birds.

Areas 7 and 8 – Klemtu, Kitasu, Bella Bella, and Bella Coola: 126 salmon streams

Area 7 has not shown the same type of slow recovery for pinks and chums as has Area 6. There does appear to be a differential between coastal interior streams in Area 7, with the earlier coastal streams doing better. But this is just ‘eye-balling’ the information; do not read too much into it. The two chum hatcheries in Area 7 saw very poor returns, as did all the wild systems.

Only 580 pink salmon returned to Neekas Inlet after the 2022 ‘die-off’ event. Neekas had a decent return in 2022 but most did not successfully spawn. This provides another example of how we must consider the impacts of climate change risks to salmon, even when they appear to return at sustainable levels.

Area 8 pinks, finally, showed some sign of life after years of terrible returns (other than 2020). Could this be a sign of a resurgence of even year pinks? I certainly hope so. Having said this, pink returns were only just over one-half the one million escapement target. They have a long way to go.

Wild chum returns to Bella Coola and Kimsquit also showed strength in 2024. However, the chum returns to other wild chum systems were poor. This once again illustrates the risk of generalizing salmon returns, even within one area, or of basing fishery openings on general abundance that may mask conservation concerns for specific streams or areas.

Area 8 sockeye returns were terrible. Chinook returns were two-thirds of their target in the Bella Coola/Atnarko systems, but poor in the Dean Watershed. And, speaking of the Dean River, all reports are that it had a very good steelhead return.

Area 8 was one of the few areas on the coast where any of the 78 Pacific Salmon Strategy Initiative (PSSI) long term conservation closures, announced by DFO with much fanfare in 2021, remain in effect.

Areas 9 and 10 – Rivers and Smith Inlets, Dawson’s Landing, and Wuikinuxv: 73 salmon streams

There is a paucity of return information for both Areas 9 and 10. The little information there is for Area 9 suggests poor returns for all species. There is next to no information available for Area 10. Both Areas 9 and 10 saw major gillnet fisheries for sockeye when I began my career. The collapse of these fisheries, and the migration of these largely southern resident fleets into the Nass and Skeena fisheries, initiated the decline in what was then a largely local Nass/Skeena fishery populated by First Nations.

I would like to acknowledge the dozens of DFO and First Nations managers, technicians, and scientists who accumulate and present the massive amount of data and information used in my recaps. My task is to corral the information contained in the myriad of reports in a manner and context that is useful to you, the reader. Our thanks should go to them. Any criticisms of omissions, mistakes, or bias should be directed at me. It’s okay. I won’t be too offended. As my best-before date on this planet approaches, observing spawning salmon in a local stream resonates. Taking offence, less so.

Part One

Reflecting on the 2024 Salmon Season

Sustainable Fisheries Management & Climate Change Solutions

Adapting to an uncertain future

Other News

SkeenaWild Executive Director – Job Posting

We’re hiring for a new Executive Director. The Executive Director is responsible for leading and managing the Trust to achieve its mission of conserving wild…

A New Chapter for SkeenaWild

New Chapter for SkeenaWild A Note From Executive Director, Greg Knox Dear Friends, After eighteen years as Executive Director of SkeenaWild Conservation Trust, I am…

Greg Taylor 2024 Salmon Fishery Recap: Part Two

In the second instalment of his annual salmon recap, Greg Taylor dives into the 2024 returns across B.C.’s North and Central Coast. From the Skeena…

Greg Taylor 2024 Salmon Fishery Recap: Part One

Greg Taylor 2024 Salmon Fishery Recap: Part One Reflecting on the 2024 Salmon Season Written by Greg Taylor, Fisheries Advisor It is that time of…

SkeenaWild Executive Director – Job Posting

We’re hiring for a new Executive Director. The Executive Director is responsible for leading and managing the Trust to achieve its mission of conserving wild…

A New Chapter for SkeenaWild

New Chapter for SkeenaWild A Note From Executive Director, Greg Knox Dear Friends, After eighteen years as Executive Director of SkeenaWild Conservation Trust, I am…

Greg Taylor 2024 Salmon Fishery Recap: Part Two

In the second instalment of his annual salmon recap, Greg Taylor dives into the 2024 returns across B.C.’s North and Central Coast. From the Skeena…

Greg Taylor 2024 Salmon Fishery Recap: Part One

Greg Taylor 2024 Salmon Fishery Recap: Part One Reflecting on the 2024 Salmon Season Written by Greg Taylor, Fisheries Advisor It is that time of…